From early inventions to modern tools

that make digital spaces accessible

Screen readers and braille devices are tools that help people access digital content when reading text visually is difficult or not possible. These technologies are essential for digital accessibility and inclusive design, letting people use websites, documents, apps, and online services independently.

They aren’t just for people who are blind. They also help people with low vision, dyslexia, cognitive disability, learning disability, brain injury, or anyone who finds it hard to process visual information. Accessible design gives users choices — whether they listen, read braille, or do both.

At DASAT, we know that screen readers and braille devices are more than tools. They reveal whether a website or digital system is truly accessible in real life. Two of our team rely on screen readers and braille devices to complete their work. Learn more about our digital accessibility audits and how they help organisations make technology usable for everyone.

How Screen Readers Work

Screen readers turn digital content into spoken words or braille by reading the underlying structure of a page. They don’t rely on visual information, but on headings, links, buttons, paragraphs, and form labels.

A screen reader can:

- Read text aloud or to a braille display

- Announce headings and page sections

- Identify links and buttons

- Read form labels and instructions

- Describe images when text alternatives are available

Users control screen readers with keyboards, touch gestures, or shortcuts. This flexibility also helps people with dyslexia or cognitive challenges reduce overload and improve comprehension.

The History of Screen Readers

Screen readers started as tools for early computers, which were largely inaccessible because they relied on visual interfaces. Early screen readers focused on reading text line by line for blind users.

Jim Thatcher, an accessibility researcher, helped develop early screen readers in the 1980s by making them interpret text logically, not just visually. (Knowbility)

JAWS: A Leading Screen Reader

JAWS (Job Access With Speech) is one of the most widely used screen readers today. It was created in the late 1980s by Ted Henter, a former motorcycle racer who lost his sight in an accident. He co-founded Henter-Joyce with Bill Joyce to develop assistive technology for blind computer users. (The Verge)

JAWS ran first on MS-DOS, then JAWS for Windows was released in 1995, designed for graphical interfaces. Features like scripting and dual cursors made it easier to navigate complex applications. Today, JAWS continues to support modern software, web access, and braille devices.

NVDA: Free and Open-Source Screen Reader

NVDA (Nonvisual Desktop Access) was created in 2006 by blind Australians Michael Curran and James Teh to make screen readers free and accessible. They founded the not-for-profit NV Access to maintain NVDA. (NV Access)

NVDA has been translated into more than 55 languages and is used in over 175 countries. Its community-driven development ensures that screen readers remain accessible, up-to-date, and responsive to real user needs.

What Are Braille Devices?

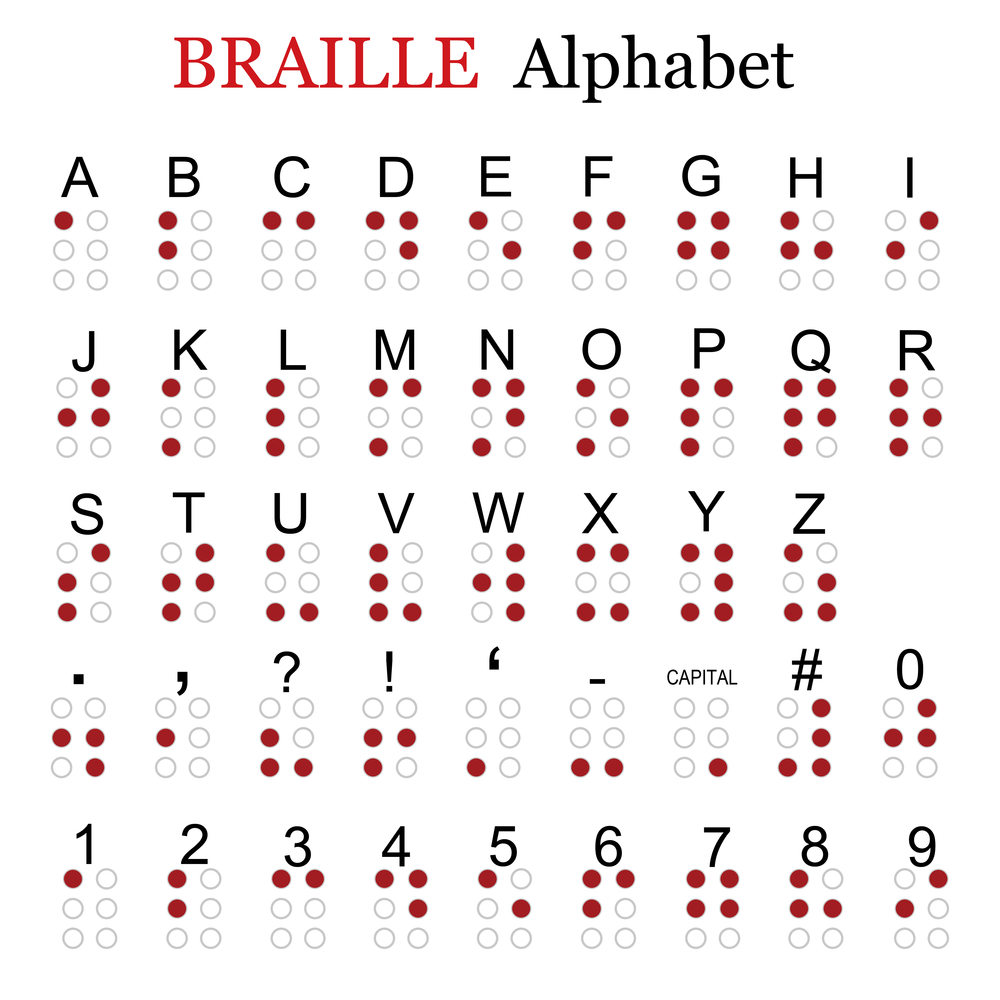

Braille devices, often called refreshable braille displays, convert digital text into braille characters using rows of small pins. The display updates in real time as a screen reader reads the content, allowing users to read by touch.

They are often used alongside screen readers for accuracy, spelling, layout details, and privacy. Braille devices are especially helpful for people who are deafblind or prefer tactile reading.

A Short History of Braille and Braille Devices

Braille was invented in the early 1800s by Louis Braille, a young man in France who was blind. He developed a system of raised dots that could be read with the fingertips. Braille quickly became the foundation for literacy and independence.

Early braille tools included slates and styluses for writing raised dots and mechanical braille typewriters to make writing faster.

In the 20th century, inventors like David Abraham worked with the American Printing House for the Blind to improve braille writing technology. These innovations led to modern electronic refreshable braille displays, which now work with computers, tablets, and smartphones for real-time digital access.

Common Screen Readers Today

- JAWS – Professional-grade screen reader widely used in workplaces and schools

- NVDA – Free, open-source screen reader used globally

- VoiceOver – Built into Apple devices

- TalkBack – Built into Android devices

- Narrator – Built into Windows

These tools work with braille devices, speech output, and navigation methods to support diverse users.

Who Uses Screen Readers and Braille Devices?

People who have vision processing issues are the main group of screen reader users. That includes:

- People who are blind or have low vision

- People who are deafblind

- People with dyslexia

- People with cognitive or learning disability

- People with brain injury or neurological conditions

- Older people with vision or processing challenges

These technologies help users participate fully in education, work, community life, and everyday tasks.

Why Digital Accessibility Matters

Screen readers and braille devices only work if websites and apps are designed accessibly. Accessible content includes:

- Correctly ordered headings

- Descriptive link text

- Properly labelled form fields

- Text alternatives for images

- Logical layout and navigation

Accessibility is not just about compliance — it is about inclusion, dignity, and usability. Learn how DASAT can help with accessibility audits led by people with disability.

The Bottom Line

Screen readers and braille devices have transformed digital access for millions of people around the world. From Louis Braille’s raised-dot system to modern tools like JAWS and NVDA, these technologies show how innovation and accessibility can work together to create independence and inclusion. At DASAT, we know that accessibility is not just about tools — it’s about designing websites, apps, and services that everyone can use. By testing and improving digital experiences with real users, organisations can ensure that their content is truly usable, inclusive, and welcoming to all.